The Enabling Act allowed the Reich government to issue laws without the consent of Germany’s parliament, laying the foundation for the complete Nazification of German society. The law was passed on March 23, 1933, and published the following day. Its full name was the “Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Reich.”

This content is available in the following languages

Close language menu View this term in the glossaryThe Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Reich is also known as the Enabling Act. Passed on March 23, 1933, and proclaimed the next day, it became the cornerstone of Adolf Hitler's dictatorship. The act allowed him to enact laws, including ones that violated the Weimar Constitution, without approval of either parliament or Reich President von Hindenburg.

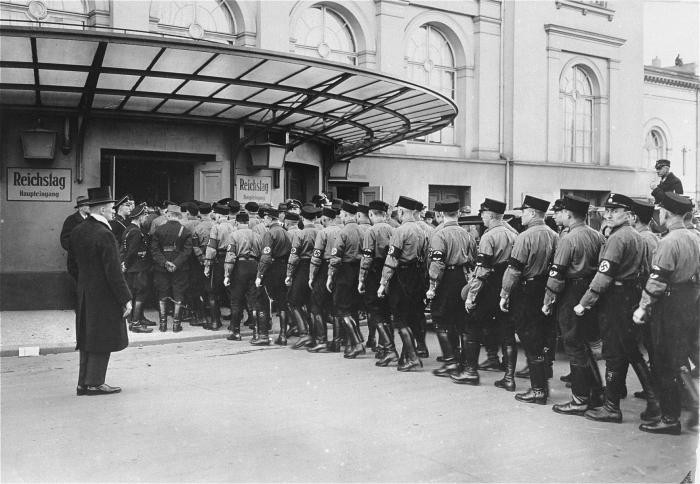

Since the passage of this law depended upon a two-thirds majority vote in parliament, Hitler and the Nazi Party used intimidation and persecution to ensure the outcome they desired. They prevented all 81 Communists and 26 of the 120 Social Democrats from taking their seats, detaining them in so-called protective detention in Nazi-controlled camps. In addition, they stationed SA and SS members in the chamber to intimidate the remaining representatives and guarantee their compliance. In the end, the law passed with more than the required two-thirds majority, with only Social Democrats voting against it.

The Supreme Court did nothing to challenge the legitimacy of this measure. Instead, it accepted the majority vote, overlooking the absence of the Communist delegates and the Social Democrats who were under arrest.

In fact, most judges were convinced of the legitimacy of the process and did not understand why the Nazis proclaimed a “Nazi Revolution.” Erich Schultze, one of the first Supreme Court judges to join the Nazi Party, declared that the term “revolution” did not refer to an overthrow of the established order but rather to Hitler's radically different ideas. In the end, German judges—who were among the few who might have challenged Nazi objectives—viewed Hitler's government as legitimate and continued to regard themselves as state servants who owed him their allegiance and support.

Translated from Reichsgesetzblatt I, 1933, p. 141.

The Reichstag has enacted the following law, which has the agreement of the Reichsrat and meets the requirements for a constitutional amendment, which is hereby announced:

Article 1

In addition to the procedure prescribed by the Constitution, laws of the Reich may also be enacted by the Reich Government. This includes laws as referred to by Articles 85, Sentence 2, and Article 87 of the Constitution.

Article 2

Laws enacted by the Reich Government may deviate from the Constitution as long as they do not affect the institutions of the Reichstag and the Reichsrat. The rights of the President remain undisturbed.

Article 3

Laws enacted by the Reich Government shall be issued by the Chancellor and announced in the Reichsgesetzblatt. They shall take effect on the day following the announcement, unless they prescribe a different date. Articles 68 to 77 of the Constitution do not apply to laws enacted by the Reich Government.

Article 4

Reich treaties with foreign states that affect matters of Reich legislation shall not require the approval of the bodies concerned with legislation. The Reich Government shall issue the regulations required for the execution of such treaties.

Article 5

This law takes effect with the day of its proclamation. It loses force on April 1, 1937, or if the present Reich Government is replaced by another.

Berlin, March 24, 1933

The Reich President von Hindenburg

Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler

Reich Minister of the Interior Frick

Reich Minister of Foreign Affairs Freiherr von Neurath

Reich Minister of Finance Graf Schwerin von Krosigk